Digital Diagnosis: Health Data Privacy in the U.S. – Law and Biosciences Blog

Gabriela Rios, CLB student fellow, LLM (expected 2025)

Imagine waking up to find your most intimate health details splashed across the internet for all to see. For over 1 million Connecticut residents, this nightmare became a reality on February 4, 2025, when a massive healthcare data breach exposed their personal information, including Social Security numbers, test results, diagnosis, treatment information, among others[1]. This incident is not isolated – it’s part of a disturbing trend where our digital health footprints are increasingly vulnerable to exploitation [2]. From the apps on our phones to the wearables on our wrists, every interaction leaves a trace, forming a complex constellation of our most personal information. In an era where our health data is as valuable as gold but as fragile as glass, understanding the landscape of health data privacy has never been more crucial.

In the following sections, we’ll unpack the complexities of health data privacy in the United States. First, we’ll address the increasing nation-wide concern, then move on to an overview of the current federal and state legislative landscape on both general and health privacy, followed by some positive and negative aspects of the current framework before concluding with the challenges that lie ahead and the motivation that should drive future efforts in protecting health data. This exploration will support the central claim: Protecting health data must be foundational principle to sustaining patient trust and ensuring equitable access to care in an increasingly data driven world.

Introduction

Privacy in the United States has become increasingly complex and critical, especially in the digital age. As technology advances and data becomes a more valuable commodity, the legal framework governing privacy rights and data protection in the U.S. has struggled to keep pace. Unlike many other nations, the U.S. does not have a comprehensive federal privacy law, and it has relied on a growing patchwork of sector-specific regulations and state laws.

The healthcare sector has been one of specific concern and interest for all privacy matters over the years, due to various factors such as the inherently sensitive nature of the information processed; the increased reliance on electronic and digital systems; and moreover, the potential for misuse or unauthorized disclosure and the impacts it can have on the individual.

Various nationwide surveys have examined public attitudes towards health data privacy, finding concern among consumers about how their personal data, and particularly their health data is processed. One survey is the “Corporate Data Responsibility – Bridging the consumer trust gap”, a report created in 2021 by KPMG, in which 86% of the general population surveyed reported increasing concern about data privacy.[3] Another survey conducted by Trusted Future in 2022 highlights that 82% of respondents were concerned about their health data being sold without their consent and being shared without their permission[4]. This concern has certainly grown over the years and have resulted in legislative initiatives as a response.

A not-so-brief Context

The federal panorama

General Privacy in the Federal Level

Most countries have approached privacy in a comprehensive manner, with national privacy laws that apply broadly across sectors, in line with the most recent IAPP reports of the International Association of Privacy Professionals (IAPP), 144 countries have enacted national privacy laws translating into 82% of the world’s population being covered under some form of national data privacy legislation[5]. Most of these countries have adopted a data subject and rights-based approach to data protection, emphasizing individual rights of action and strict enforcement mechanisms. It is difficult to pinpoint specifically why a federal privacy law has not been enacted, some authors argue it might be due to “(…) differing political ideologies, industry interests, and legislative gridlock in Congress (…)” [6], however, this approach seems reasonable and consistent with how the U.S. federal system grants power to the states.

The U.S. came the closest it has been to passing a comprehensive privacy law, with the American Privacy Rights Act of 2024 but the effort was unsuccessful, maintaining a sector-specific approach in the federal level (please refer to Annex 1 for further detail) and relying on the state’s power to regulate such matter.

Healthcare-Specific Privacy Laws:

Three of the laws pertain specifically to the healthcare sector: (i) Health Insurance Portability and Accountability (hereinafter HIPAA)[7]; (ii) Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act[8]; and (iii) Health Information Technology for Clinical and Economic Health[9].

HIPAA was enacted in 1996, and it required the Department of Health and Human Services to create regulations that would provide national standards for the protection of health information, ensuring consistency across the country, a task it took HHS until 2003 to complete and that, even then, didn’t become effective for most covered entities until 2005. However, HIPAA has faced criticism over the years starting by it being out of synch with modern digital technologies used in the sector, its limited scope to covered entities, not covering non-traditional parties that collect and process health data [10].

State Privacy Laws:

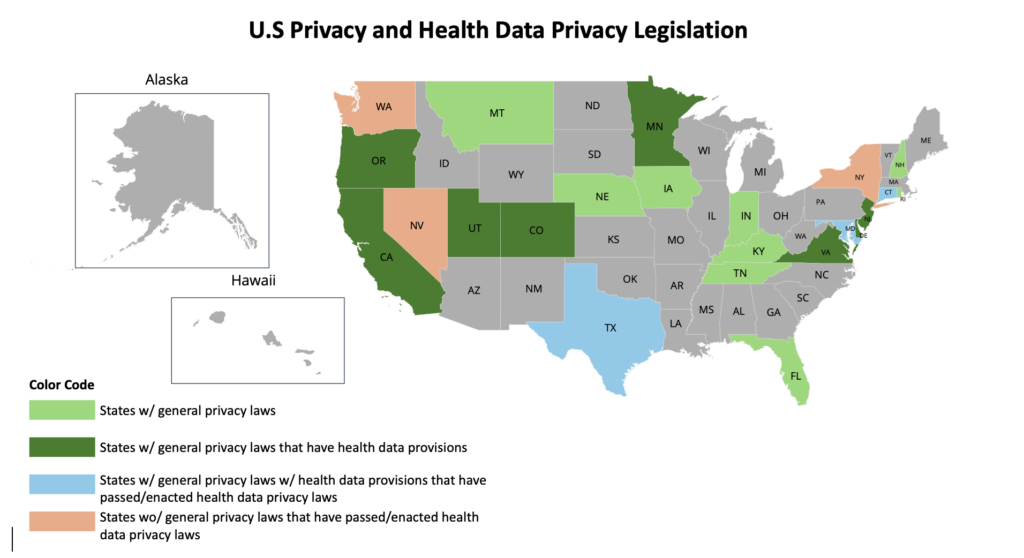

The States have then taken on the burden of creating regulations around privacy matters. As of 2025, 19 states have enacted comprehensive privacy laws (Annex 2) with some of them including provisions for health-related data (Annex 3), but there has been a slow increase in Health Data-Specific legislation (Annex 4) in creating specific regulations for health data (Annex 4).

The previous leaves us with something like this:

The most recent legislative advance comes from New York, as, last month, on January 22nd, the New York State legislature passed the New York Health Information Privacy Act (hereinafter “NY HIPA”), which if signed into law, would join the growing trend of Health Data-Specific legislations. Most of these health-data specific laws have various similarities, starting by their core objective: protecting consumer health data not covered by HIPAA. The clear main concern is the processing of consumer health data in non-traditional health care contexts like wearable and medical device providers, consumer and digital health companies[11]. Additionally, these laws mandate regulated entities to obtain consent from consumers, forbid selling health data without a separate authorization, grant the right to consumers to access, delete and correct their health data.

However, NY HIPA has broadened the scope of both the entities and the health data covered. First, unlike other state laws, it does not have a revenue, jurisdiction or processing threshold. Similarly, the definition of “Regulated Health Information” is considerably broad, as it includes “any information that is reasonably linkable to an individual, or a device, and is collected or processed in connection with the physical or mental health of an individual. Location or payment information that relates to an individual’s physical or mental health or any inference drawn or derived about an individual’s physical or mental health that is reasonably linkable to an individual, or a device, shall be considered, without limitation, regulated health information (…)”[12]

Additionally, the law has stricter and detailed requirements for obtaining authorization from consumers, unlike the opt-in consent requirement of other states, the law brings a complete list of elements that such authorizations must have to comply. As noted by experts on the subject “NY HIPA is positioned to be among the most extensive consumer health data privacy laws in the country”[13].

What does all this mean

The good:

As the awareness and concern over the protection of health data increases around the world and specifically in the U.S., more states could jump on the trend of regulating this specific sector, promoting a framework of trust, transparency and security for citizens regarding their health data and their ability to decide over it, as so New Mexico and Vermont have introduced new consumer health privacy bills this month.

It is unlikely that the regulatory momentum stops, especially having into account the demand for healthcare apps (with an estimate of a quarter of US internet users using healthcare apps[14]) and the rise and impact of AI in both traditional and non-traditional health care services. As the EU AI Act has shown us so far, privacy and data protection are key aspects of AI regulation, so as the technology evolves, and its applications broaden – both generally and in the healthcare sector – regulatory initiatives are expected to include privacy provisions.

The “bad”:

In general, the fragmented approach to privacy in the U.S. creates a huge financial and technical burden for entities that process personal data when attempting to comply with all state requirements because there is not a harmonized framework that allows a one-size-fits all privacy compliance program.

The big challenge comes to those who had fallen outside of the scope of HIPAA since its enactment, who have for years, collected, processed, stored and sold health related data without much control and oversight, who now need to analyze the evolving legislative framework, its applicability, the impacts on their operations, determine their privacy obligations and create a compliance strategy for each state.

Conclusion

Health data privacy is a critical safeguard that must be sought after in modern healthcare, balancing the value of medical innovation with the right to privacy. The sensitivity of the information – spanning conditions, treatments, genetic profiles and even inferred data from health apps – increasingly demand protections to prevent discrimination, exploitation and breaches of trust.

The regulatory discussions highlight HIPAA’s limitations in addressing a fast-moving digital ecosystem, where AI-drive analytics, consumer health tech and cross-sector data sharing outpace decade-old frameworks. States like Washington and now New York, have stepped in with laws targeting such gaps, however, this fragmented patchwork – which has now become a household term – creates compliance complexity and underscores the need for cohesive federal action. Without harmonized standards, the risk of data breaches, algorithmic bias, re-identification, which all lead to the loss of public trust threatens both individual rights and the ethical advancement of healthcare innovation.

Protecting health data must be more than just a legal obligation, it must be foundational principle to sustaining patient trust and ensuring equitable access to care in an increasingly data driven world.

Annexes

Annex 1 – Federal-level general privacy laws

Note: The column of Privacy Focus establishes whether a law is “direct” or “indirect”. Those labeled as “direct” are the ones that are aimed to explicitly create a privacy framework, those labeled as “indirect” are the ones that have privacy provisions in a legislation with a broader scope.

| Name of Law | Sector | Date Enacted | Privacy Focus |

| Federal Trade Commission Act (FTC Act) | Consumer Protection | 1914 | Indirect |

| Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) | Credit/Consumer Reporting | 1970 (amended 2003) | Direct |

| Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (Section 501) | Federal Employment (Disability Privacy) | 1973 | Indirect |

| Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) | Education | 1974 | Direct |

| Privacy Act of 1974 | Federal Government Records | 1974 | Direct |

| Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) | National Security | 1978 | Indirect |

| Right to Financial Privacy Act (RFPA) | Financial Records | 1978 | Indirect |

| Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA) | Electronic Communications | 1986 | Direct |

| Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) | Cybersecurity | 1986 | Indirect |

| Stored Communications Act (SCA) | Electronic Data Storage | 1986 | Indirect |

| Video Privacy Protection Act (VPPA) | Video Rental/Streaming | 1988 | Direct |

| Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) | Employment/Public Services | 1990 | Indirect |

| Telephone Consumer Protection Act (TCPA) | Telemarketing | 1991 | Direct |

| Driver’s Privacy Protection Act (DPPA) | Motor Vehicle Records | 1994 | Direct |

| Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) | Healthcare | 1996 | Indirect |

| Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) | Children’s Online Data | 1998 | Direct |

| Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) | Financial Services | 1999 | Direct |

| E-Government Act of 2002 (Section 208) | Federal Websites | 2002 | Indirect |

| CAN-SPAM Act | Commercial Email | 2003 | Direct |

| Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) | Employment/Health Insurance | 2008 | Direct |

| HITECH Act (Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health) | Health IT | 2009 | Direct |

| Cybersecurity Information Sharing Act (CISA) | Cybersecurity Threat Sharing | 2015 | Indirect |

Annex 2 – State-level general privacy laws

| State | Name of Law | Date Enacted |

| California | California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) | June 28, 2018 |

| Virginia | Consumer Data Protection Act (CDPA) | March 2, 2021 |

| Colorado | Colorado Privacy Act (CPA) | July 7, 2021 |

| Utah | Utah Consumer Privacy Act (UCPA) | March 24, 2022 |

| Connecticut | Connecticut Data Privacy Act (CTDPA) | May 10, 2022 |

| Iowa | Iowa Consumer Data Protection Act (ICDPA) | March 28, 2023 |

| Indiana | Indiana Consumer Data Protection Act (INCDPA) | May 1, 2023 |

| Tennessee | Tennessee Information Protection Act (TIPA) | May 11, 2023 |

| Montana | Montana Consumer Data Privacy Act (MCDPA) | May 19, 2023 |

| Florida | Florida Digital Bill of Rights (FDBR) | June 6, 2023 |

| Texas | Texas Data Privacy and Security Act (TDPSA) | June 18, 2023 |

| Oregon | Oregon Consumer Privacy Act (OCPA) | July 18, 2023 |

| Delaware | Delaware Personal Data Privacy Act (DPDPA) | September 11, 2023 |

| New Jersey | New Jersey Data Privacy Act (NJDPA) | January 16, 2024 |

| New Hampshire | New Hampshire Privacy Act (NHPA) | March 6, 2024 |

| Kentucky | Kentucky Consumer Data Protection Act (KCDPA) | April 4, 2024 |

| Nebraska | Nebraska Data Privacy Act (NEDPA) | April 17, 2024 |

| Maryland | Maryland Online Data Privacy Act (MODPA) | May 9, 2024 |

| Minnesota | Minnesota Consumer Data Privacy Act (MCDPA) | May 19, 2024 |

| Rhode Island | Rhode Island Data Transparency and Privacy Act | June 25, 2024 |

Annex 3 – General Privacy Laws with Health Data Provisions:

| State | Name of Law | Health Data Sections/Purpose |

| California | CCPA (as amended by CPRA) | Health data classified as “sensitive personal information” requiring opt-in consent (§1798.121, §1798.140(ae)) |

| Virginia | CDPA | Health data as “sensitive data” requiring consent (§59.1-575) |

| Colorado | CPA | Health data included in “sensitive data” requiring heightened protections (§6-1-1303(24)) |

| Connecticut | CTDPA | Health data defined as “sensitive data” with opt-in consent (§42-517) |

| Utah | UCPA | Health data protected under “sensitive data” provisions (§13-61-302) |

| Oregon | OCPA | Health data as “sensitive data” requiring consent (§646A.600) |

| Delaware | DPDPA | §12D-103(c)(6): Health data used for public health activities exempted under HIPAA |

| Minnesota | MCDPA | §235O.03(2)(a)(5): Health data intermingled with HIPAA-protected data exempted |

| New Jersey | NJDPA | §56:8-166: Health data classified as “sensitive” with consent requirements |

| Maryland | MODPA | §14-4603: Health data exempted if maintained as HIPAA-protected information |

Annex 4 – States with Health Data Specific Legislation

| State | Name of Law | Date Enacted | Scope & Purpose |

| Washington | My Health My Data Act (MHMD) | April 27, 2023 | Protects consumer health data (e.g., reproductive health) not covered by HIPAA. Bans geofencing. |

| Nevada | SB 370 (Consumer Health Data Privacy) | June 16, 2023 | Requires consent for collection/sharing of health data; narrower than Washington’s law. |

| Connecticut | Amendments to CTDPA (SB 3) | June 7, 2023 | Expands protections for consumer health data, including mental health and telehealth. |

| Maryland | SB 786 (Electronic Health Record Privacy) | May 8, 2023 | Regulates EHR data sharing and requires transparency for health data brokers. |

| Texas | HB 300 (Health Data Privacy Amendments) | June 14, 2024 | Strengthens protections for biometric and genetic data collected by healthcare providers. |

| New York | NY Health Information Privacy Act (NY HIPA) | Pending governor’s signature | Regulates “regulated health information” (RHI), including mental health data from apps and wearables. |

Bibliography

Alder, Steve. “2024 Healthcare Data Breach Report.” The HIPAA Journal (blog), January 30, 2025.

ASPE. “Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996,” August 20, 1996.

“Bill Search and Legislative Information | New York State Assembly.” Accessed February 22, 2025.

EMARKETER. “Consumers Use Mobile Apps to Track Fitness, Health.” Accessed February 23, 2025.

“Identifying Global Privacy Laws, Relevant DPAs | IAPP.” Accessed February 22, 2025.

KPMG. “Corporate Data Responsibility: Bridging the Consumer Trust Gap,” August 2021.

“New York’s Health Information Privacy Act Aims to Strictly Regulate Consumer Health Data | Insights | Ropes & Gray LLP.” Accessed February 22, 2025.

“Over 1 Million Connecticut Residents Impacted by Healthcare Data Breach – NBC Connecticut.” Accessed February 24, 2025.

Rights (OCR), Office for Civil. “HITECH Act Enforcement Interim Final Rule.” Page, October 28, 2009.

“The Good, The Bad, The Nonexistent: Reviewing US State Data Privacy Laws,” November 3, 2023.

Trusted Future. “Survey Data: Connected Healthcare.” TRUSTED FUTURE (blog), December 12, 2022.

US EEOC. “Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008.” Accessed December 2, 2024.

Villar, Reynaldo. “Does HIPAA Have the Muscle to Protect Patient Rights? – Calcium.” Calcium, May 22, 2019.

[1] “Over 1 Million Connecticut Residents Impacted by Healthcare Data Breach – NBC Connecticut,” accessed February 24, 2025,

[2] Steve Alder, “2024 Healthcare Data Breach Report,” The HIPAA Journal (blog), January 30, 2025,

[3] KPMG, “Corporate Data Responsibility: Bridging the Consumer Trust Gap,” August 2021,

[4] Trusted Future, “Survey Data: Connected Healthcare,” TRUSTED FUTURE (blog), December 12, 2022,

[5] “Identifying Global Privacy Laws, Relevant DPAs | IAPP,” accessed February 22, 2025,

[6] “The Good, The Bad, The Nonexistent: Reviewing US State Data Privacy Laws,” November 3, 2023,

[7] “Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996,” ASPE, August 20, 1996,

[8] “Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008,” US EEOC, accessed December 2, 2024,

[9] Office for Civil Rights (OCR), “HITECH Act Enforcement Interim Final Rule,” Page, October 28, 2009,

[10] Reynaldo Villar, “Does HIPAA Have the Muscle to Protect Patient Rights? – Calcium,” Calcium, May 22, 2019,

[11] “New York’s Health Information Privacy Act Aims to Strictly Regulate Consumer Health Data | Insights | Ropes & Gray LLP,” accessed February 22, 2025,

[12] “Bill Search and Legislative Information | New York State Assembly,” accessed February 22, 2025,

[13] “New York’s Health Information Privacy Act Aims to Strictly Regulate Consumer Health Data | Insights | Ropes & Gray LLP.”

[14] “Consumers Use Mobile Apps to Track Fitness, Health,” EMARKETER, accessed February 23, 2025,

link